Measuring Mountain Everest: The World’s Highest Peak, From the Great Trigonometric Survey to Modern Measurements

Measuring Mountain Everest: The World’s Highest Peak, From the Great Trigonometric Survey to Modern Measurements

From Radhanath Sikdar’s groundbreaking 1852 calculation to the 2020 Nepal-China joint survey, the history of Everest’s measurement reflects both scientific brilliance and overlooked contributions.

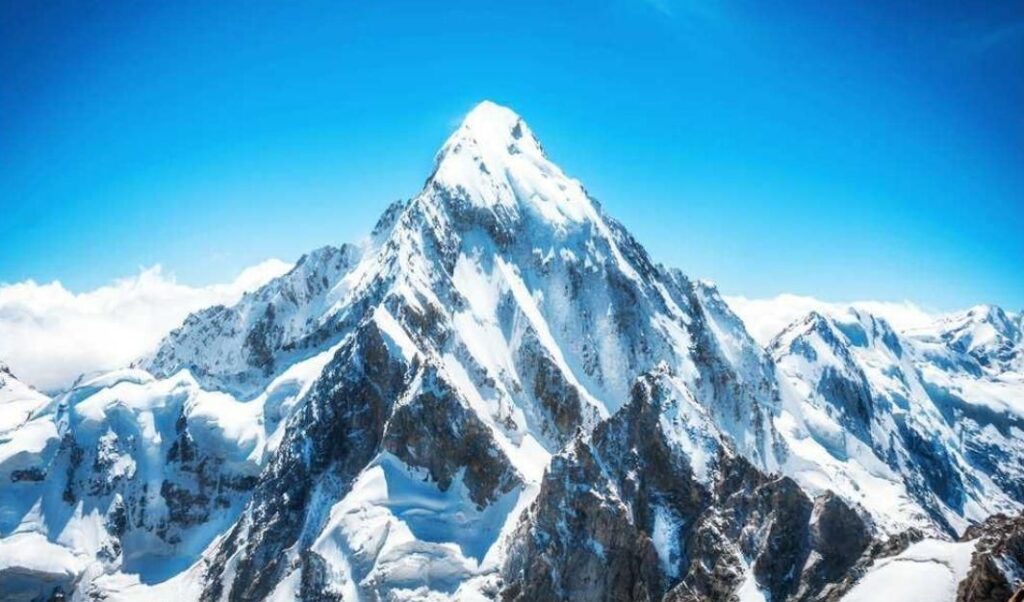

The official height of Mount Everest stands at 8,848.86 meters (29,031.69 feet), a figure jointly declared by Nepal and China in December 2020. The measurement, based on advanced technologies such as GPS, BeiDou navigation systems, and laser theodolites, resolved earlier discrepancies and was later endorsed by international organizations including the National Geographic Society. This updated figure reflects a slight increase from earlier estimates, attributed partly to geological shifts and improved accuracy of instruments.

The Origins: The Great Trigonometric Survey

The story of Everest’s recognition as the world’s highest peak begins with the Great Trigonometric Survey of British India, which commenced in 1808. The survey was one of the most ambitious scientific undertakings of its time, aiming to map the entire Indian subcontinent using trigonometry and astronomical observations.

In 1852, an Indian mathematician and surveyor, Radhanath Sikdar, working under this survey, made a breakthrough. Applying complex trigonometric calculations and the Method of Least Squares to enormous datasets, Sikdar determined that Peak XV—later named Mount Everest—was higher than Kanchenjunga, then believed to be the tallest mountain. His work was revolutionary because he managed to establish this fact without physically visiting the mountain, relying entirely on mathematics, precision, and data.

The Unsung Hero: Radhanath Sikdar

While Sikdar’s calculation was central to the discovery, his role was largely overshadowed. The official recognition came only in 1856, four years after he submitted his findings, as the British surveyors were initially hesitant to trust the results. Ultimately, the peak was named after Sir George Everest, the Surveyor General of India until 1843, despite the fact that Everest himself had never seen the mountain. The naming was championed by Andrew Scott Waugh, Everest’s successor, whose reputation ensured the adoption of “Mount Everest” internationally.

This decision has long been criticized as an example of colonial erasure of Indian contributions. In Nepal, the mountain is revered as Sagarmatha, while in Tibet, it is called Qomolangma (Chomolungma), both names predating its colonial title.

Modern Measurement Efforts

Since Sikdar’s landmark calculation, Everest’s height has been re-measured several times, with estimates ranging from 8,840 meters to 8,850 meters, depending on whether snow cap or rock base was considered. The 2020 joint survey by Nepal and China brought clarity after decades of debate. The survey teams climbed Everest with modern instruments, deploying Global Navigation Satellite Systems (GNSS) and radar technologies to ensure unprecedented accuracy.

Legacy of Science and Symbolism

Mount Everest today symbolizes both the progress of scientific measurement and the legacy of unsung contributions. While the world knows it as the tallest peak, the story behind its discovery is also a reminder of how local talent like Radhanath Sikdar shaped global knowledge but was overshadowed in colonial narratives.

From a mathematical desk in Kolkata in 1852 to satellite-enabled surveys in 2020, the measurement of Everest remains one of the most compelling chapters in the history of science, exploration, and human determination.